Contemporary theological accounts of gender—complementarianism and egalitarianism as previously outlined—serve as part background to my own proposed doctoral research: One Flesh: A Literary and Socio-Rhetorical Study of the Pauline (and Deutero-Pauline) Marriage Texts.[1] Expressed more simply, I am exploring the apostle Paul’s writings about marriage with reference to their first-century social setting. Given the intersection between my own proposed research and this wider gender debate, what follows are some observations of the current literature and how a New Testament study on marriage might contribute to an evangelical theology of gender.

- The discussion in the literature is weighted towards ecclesial (that is, church related) texts rather than those related to marriage. However, this distinction, often taken for granted in the literature, merits closer examination for at least two reasons. First, the Greek terms gynē and anēr can be translated as woman or wife and man or husband respectively. The interpreter must make a translation decision as to which texts are appealing to the marriage relationship and which have a more generic reference. Secondly, because Christ-followers in the New Testament era mostly met together in private homes, drawing too sharp a distinction between ecclesial and household settings could be anachronistic. Yet, even when such factors are accounted for, a study with special focus on the apostle Paul’s marriage theology offers an opportunity to test theological accounts of gender and propose fresh lines of enquiry based upon pertinent texts.

- Where the literature does address texts about marriage it is the household codes,[2] and in particular Ephesians 5–6, which receive the most attention. Recent socio-rhetorical readings have, in my view, persuasively shown that the New Testament household codes subvert, and even reverse, ancient hierarchical household norms.[3] Curiously, as far as I can tell, there has been little critical engagement with such scholarship from complementarian scholars. Moreover, the extensive treatment of marriage by Paul in 1 Cor 7:1–40 is under-represented in the literature and all but absent from complementarian accounts of gender.[4]

- The importance of the “one flesh” (Gen 2:24) motif for Pauline marital theology is under-developed in the literature. This creation ideal is referenced in 1 Cor 6:16 as a reason to “flee from immorality” (NIV) and Jesus’ appropriation of it (Matt 19:4–9; Mark 10:6–12) is likely alluded to when Paul notes the Lord’s command (1 Cor 7:10). This heightens the possibility that Paul’s exhortation to the married in 1 Cor 7:2–6 is similarly informed by Paul’s own reflections on this theological concept of “one flesh”. Moreover, while discussion about the head/body metaphor in Eph 5:22–33 is prominent in the literature the complete quotation of Gen 2:24 (Eph 5:31) as part of Paul’s concluding summary invites further analysis.

- Although the term “one flesh” does not appear elsewhere in Paul’s writings, the Creation story it references may serve as the literary background of 1 Cor 11:2–16 and 1 Tim 2:8–15. That is, one must make an interpretive decision whether these Pauline texts are referencing marriage, wider gendered relationships, or both.

- While most of the literature is concerned with roles within gendered relationships, there is little discussion about the ontological essence of maleness and femaleness which gives rise to such functions. Put another way, what is the nature of the order of relations between men/women and husbands/wives? Commonly used descriptive terms such as complementarity, mutuality, equality, and hierarchy each require more essential anthropological claims about gender. Complementarian scholarship has been reluctant to make such claims, limiting itself to suggesting that physiological and neural differences predispose individuals towards certain gendered behaviours.[5] Egalitarian scholarship has criticised complementarianism for being indebted to Aristotelian conceptions of gender.[6] Moreover, theologically informed social-scientific literature is emerging which seeks to critique complementarian claims by testing whether such marital models are correlated with outcomes that are “good”.[7]

I believe that a detailed exegetical study of Paul’s marriage texts offers an opportunity to test theological accounts of gender. More precisely, my doctoral proposal seeks to (1) evaluate the significance of the “one flesh” Genesis ideal, and associated Creation story, for Pauline marital theology; (2) demonstrate the relevance and application of Paul’s marital theology with reference to its social setting; and (3) evaluate historical and contemporary theological conceptions of the order of relation between husband and wife.

The texts I intend to focus on are (1) 1 Cor 6:12–7:40; (2) 1 Cor 11:2–16 in tandem with 1 Cor 14:33b–35; (3) Eph 5:21—6:4 in tandem with Col 3:18–21; and (4) 1 Tim 2:8–15.

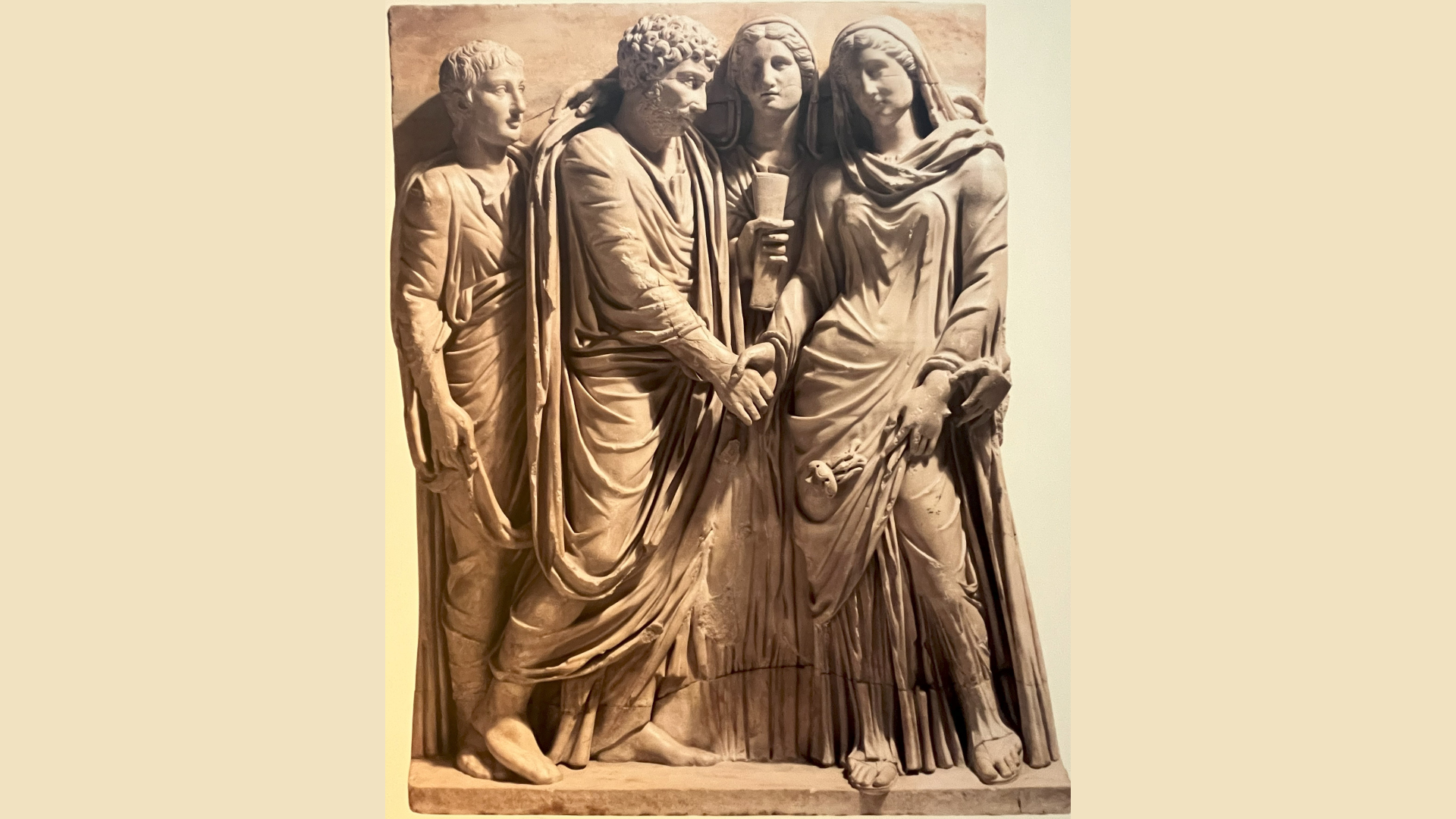

The feature image is my own taken at the British Museum and is a fragment from the front of a marble sarcophagus depicting a Roman marriage ceremony of dextrarium iunctio: the joining of hands, 2nd century AD.

[1] Deutero-Pauline refers to letters of the New Testament which, while attributed to the apostle Paul, are viewed by most critical scholars as written by Paul’s followers (e.g. Ephesians, 1 Timothy, and others).

[2] The household codes refer to those instructions in the New Testament which are addressed to pairs of Christian people in a typical Roman household: Eph 5:22—6:9, Col 3:18—4:1, 1 Pet 2:13—3:7, and perhaps also parts of 1 Timothy and Titus.

[3] A representative example is by Timothy G. Gombis, “A Radically New Humanity: The Function of the Haustafel in Ephesians,” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 48/2 (2005): 317–30.

[4] For example, in Christopher Ash’s otherwise comprehensive monograph Marriage: Sex in the Service of God (Leiscester: IVP, 2003), 1 Cor 7 features in the chapter: Intimacy and Order in the Service of God but is omitted from the list of texts which make up the chapter: God’s Pattern for Marriage.

[5] Gregg Johnson, “The Biological Basis for Gender-Specific Behaviour,” in Recovering Biblical Manhood & Womanhood: A Response to Evangelical Feminism, ed. Wayne Grudem and John Piper (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2006), 330–47. A forthcoming title by Gregg R. Allison promises to engage with philosophically significant differences between women and men. See Complementarity: Dignity, Difference, and Interdependence (Nashville, Tenn.: B&H Academic, 2025).

[6] Rebecca Merrill Groothuis, “Equal in Being, Unequal in Role: Challenging the Logic of Women’s Subordination,” in Discovering Biblical Equality: Biblical, Theological, Cultural, & Practical Perspectives, 3rd ed. Edited by Ronald W. Pierce, Cynthia Long Westfall, and Christa L. McKirland, (Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 2021).

[7] Kylie Maddox Pidgeon, “Complementarianism and Domestic Abuse: A Social-Scientific Perspective on Whether ‘Equal but Different’ is Really Equal at All,” in Discovering Biblical Equality.

An interesting read and will be most interesting to follow Scott.